I should make it clear from the start that I have no religious agenda. I’m not a believer. I’m not a committed atheist either.

For 10 years, I was an editor at Scientific American. During that time, we were diligent about exposing the falsehoods of “intelligent design” proponents who claimed to see God’s hand in the fashioning of complex biological structures such as the human eye and the bacterial flagellum. But in 2008 I left journalism to write fiction. I wrote novels about Albert Einstein and quantum theory and the mysteries of the cosmos. And ideas about God keep popping up in my books.

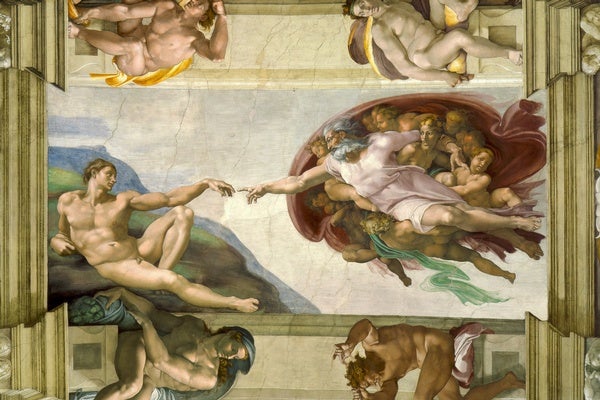

Should scientists even try to answer questions about the purpose of the universe? Most researchers assume that science and religion are completely separate fields—or, in the phrase coined by evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould, “nonoverlapping magisteria.” But as physicists investigate the most fundamental characteristics of nature, they’re tackling issues that have long been the province of philosophers and theologians: Is the universe infinite and eternal? Why does it seem to follow mathematical laws, and are those laws inevitable? And, perhaps most important, why does the universe exist? Why is there something instead of nothing?

Medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas posed similar questions in his 13th-century book Summa Theologica, which presented several arguments for God’s existence. He observed that all worldly objects can change from potential to actuality—an ice cube can melt, a child can grow—but the cause of that change must be something besides that object (warm air melts the ice cube, food nourishes the child). The history of the universe can thus be seen as an endless chain of changes, but Aquinas argued that there must be some transcendent entity that initiated the chain, something that is itself unchanging and that already possesses all of the properties that worldly objects can come to possess. He also claimed that this entity must be eternal; because it is the root of all causes, nothing else could’ve caused it. And unlike all worldly objects, the transcendent entity is necessary—it must exist.

Aquinas defined that entity as God. This reasoning came to be known as the cosmological argument, and many philosophers elaborated on it. In the 18th century, German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz described God as “as “a necessary being which has its reason for existence in itself.” It’s interesting to note that Leibniz was also a mathematician and physicist; he invented differential and integral calculus at about the same time that Isaac Newton did. (They developed the math independently.) Both Leibniz and Newton considered themselves natural philosophers, and they freely jumped back and forth between science and theology.

By the 20th century, most scientists no longer devised proofs of God’s existence, but the connection between physics and faith hadn’t been entirely severed. Einstein, who frequently spoke about religion, didn’t believe in a personal God who influences history or human behavior, but he wasn’t an atheist either. He preferred to call himself agnostic, although he sometimes leaned toward the pantheism of Jewish-Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza, who proclaimed, in the 17th century, that God is identical with nature.

Likewise, Einstein compared the human race to a small child in a library full of books written in unfamiliar languages: “The child notes a definite plan in the arrangement of the books, a mysterious order, which it does not comprehend, but only dimly suspects. That, it seems to me, is the attitude of the human mind, even the greatest and most cultured, toward God. We see a universe marvelously arranged, obeying certain laws, but we understand the laws only dimly.”

Einstein often invoked God when he talked about physics. In 1919, after British scientists confirmed Einstein’s general theory of relativity by detecting the bending of starlight around the sun, he was asked how he would’ve reacted if the researchers hadn’t found the supporting evidence. “Then I would have felt sorry for the dear Lord,” Einstein said. “The theory is correct.” His attitude was a strange mix of humility and arrogance. He was clearly awed by the laws of physics and grateful that they were mathematically decipherable. (“The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility,” he said. “The fact that it is comprehensible is a miracle.”)

But during the 1920s and 1930s, hefiercely resisted the emerging field of quantum mechanics because it clashed with his firm belief that the universe is deterministic—that is, physical actions always have predictable effects. Einstein famously criticized the indeterminacy of quantum theory by saying, God “does not play dice” with the universe. (Niels Bohr, the father of quantum mechanics, is said to have remarked, “Einstein, stop telling God what to do.”)

Although quantum theory is now the foundation of particle physics, many scientists still share Einstein’s discomfort with its implications. The theory has revealed aspects of nature that seem supernatural: the act of observing something can apparently alter its reality, and quantum entanglement can weave together distant pieces of spacetime. (Einstein derisively called it “spooky action at a distance.”) The laws of nature also put strict limits on what we can learn about the universe. We can’t peer inside black holes, for example, or view anything that lies beyond the distance that light has traveled since the start of the big bang.

Is there a place in this universe for the causative God of Aquinas and Leibniz? Or maybe the more diffuse God of Spinoza? The late particle physicist Victor Stenger addressed this question in his 2007 book God: The Failed Hypothesis. (To make his position clear, he gave the book the subtitle How Science Shows That God Does Not Exist.) Stenger quickly dismissed the theist notion of a God who responds to prayers and cures ill children, because scientists would’ve noticed that kind of divine intervention by now. Then he argued, less convincingly, against the existence of a deist God who created the universe and its laws and then stood back and watched it run.

Stenger contended that many laws of nature (such as the conservation of energy) follow inevitably from the observed symmetries of the universe (there’s no special point or direction in space, for example). “There is no reason why the laws of physics cannot have come from within the universe itself,” he wrote. Explaining the creation of the universe is trickier, though. Cosmologists don’t know if the universe even had a beginning. Instead it might’ve had an eternal past before the big bang, stretching infinitely backward in time. Some cosmological models propose that the universe has gone through endless cycles of expansion and contraction. And some versions of the theory of inflation postulate an eternal process in which new universes are forever branching off from the speedily expanding “inflationary background.”

But other cosmologists argue that inflation had to start somewhere, and the starting point could’ve been essentially nothing. As we’ve learned from quantum theory, even empty space has energy, and nothingness is unstable. All kinds of improbable things can happen in empty space, and one of them might’ve been a sudden drop to a lower vacuum energy, which could’ve triggered the inflationary expansion.

For Stenger, this theoretical possibility was evidence that God isn’t needed for Creation. “The natural state of affairs is something rather than nothing,” he wrote. “An empty universe requires supernatural intervention—not a full one.” But this conclusion seems a bit hasty. Scientists don’t fully comprehend the quantum world yet, and their hypotheses about the first moments of Creation aren’t much more than guesses at this point. We need to discover and understand the fundamental laws of physics before we can say they’re inevitable. And we need to explore the universe and its history a little more thoroughly before we can make such definitive statements about its origins.

Just for the sake of argument, though, let’s assume this hypothesis of Quantum Creation is correct. Suppose we do live in a universe that generated its own laws and called itself into being. Doesn’t that sound like Leibniz’s description of God (“a necessary being which has its reason for existence in itself”)? It’s also similar to Spinoza’s pantheism, his proposition that the universe as a whole is God. Instead of proving that God doesn’t exist, maybe science will broaden our definition of divinity.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. To spur humanity’s search for meaning, we should prioritize the funding of advanced telescopes and other scientific instruments that can provide the needed data to researchers studying fundamental physics. And maybe this effort will lead to breakthroughs in theology as well. The pivotal role of observers in quantum theory is very curious. Is it possible that the human race has a cosmic purpose after all? Did the universe blossom into an untold number of realities, each containing billions of galaxies and vast oceans of emptiness between them, just to produce a few scattered communities of observers? Is the ultimate goal of the universe to observe its own splendor?

Perhaps. We’ll have to wait and see.

This essay was adapted from the introduction to Saint Joan of New York: A Novel about God and String Theory (Springer, 2019).

"can" - Google News

December 23, 2019 at 10:29PM

https://ift.tt/2EMo987

Can Science Rule Out God? - Scientific American

"can" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2NE2i6G

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

No comments:

Post a Comment